A curious conglomerate…published in this form for the first time in Verse Wisconsin…

Lorine Niedecker’s “marriage”: Discoveries

by Sarah Busse

Jenny Penberthy, in her comprehensive Lorine Niedecker: Collected Works, notes that in 1964, Lorine Niedecker made three small, handmade books. One she gave to her old friend, Louis Zukofsky, one to her publisher, Jonathan Williams, and one she gave to fellow poet Cid Corman. As Penberthy makes clear, all of these books were similar in their contents, but not identical. Niedecker had a habit of making various types of books for friends and family. She was having trouble getting her poems published to a broader audience, and we may imagine that making these poetry books took at least some of the internal pressure off.

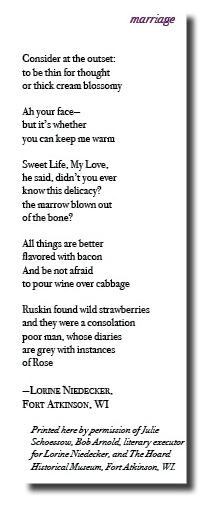

Digging around in the archives at the Hoard Museum in Fort Atkinson earlier this year, I discovered a fourth handmade book from 1964, similar in size and shape to the others, but with many textual differences. This one she gave not to a fellow poet, but to her step-daughter Julie Schoessow as a birthday gift. And the very last poem in this fourth book is “marriage,” a curious conglomerate of stanzas we recognize.

What does this small poem tell us, with its charged title? (It was unusual for Lorine to title her works at all, and even more rare for such an autobiographical reference to be made.) Is it even fair, given the private nature of such a gift, to draw any larger conclusions about her poetics, her own reading of herself? As a fellow poet, I believe it is. Any time a writer sets her own poems into book form, even as a private gift, it is a charged act. And, given the difficulty she had getting her poems into publication at all during her lifetime, we may well suspect that Niedecker made these gift books as a record of what she wanted to find its way to the world eventually. There is evidence that Lorine held some faint hope that at least one person in her husband Al’s family would help steer Lorine’s poetry into the world after Lorine’s death. In Lisa Pater Faranda’s “Between Your House and Mine”: The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, we find a letter dated March 7, 1968, in which she asks Corman for advice regarding copyright law. She ends with a postscript which states:

I can’t vouch for Al staying interested in my literary work to the extent of selling it after I’m gone, and not certainly Al’s children with possible exception of one.

A gift to Al’s daughter Julie was not necessarily meant to be kept hidden away forever.

If we accept that we may view these books not just as personal gifts, but also as documents to be studied that may well yield insights, what then do we find here, with “marriage”? First of all, this poem places itself, by virtue of its title, next to Niedecker’s more famous poem, “I married.” This latter has often been cited as proof that Niedecker had serious doubts about her own marriage, that there were tensions in her late marriage to Al Millen which she perhaps could not or would not give voice to in real life, and could only vent into poetry. But what does she say here of marriage? Let us move point by point through the poem.

To start, she “considers” options: to be “thin for thought,” and lead the ascetic life of a philosopher (which arguably she had been, for a number of years), or “thick cream blossomy,” an evocative phrase which combines the largesse of the kitchen with the fecund outdoor world. She sets up as a choice to embrace the sensual, sensory world, or to turn away from it. This is a choice every writer faces to some degree. For many years, we know Niedecker purposely remained “thin for thought.”

With the second stanza, a sudden interruption: “Ah your face—” but then the poem draws back from this attraction to consider “whether / you can keep me warm.” We move from a momentary (perhaps surprising) flare of physical attraction to the longer term care and consideration involved in commitment.

In the third stanza, almost as response to the question in stanza two, we hear “his” voice. Note that in this version of the stanza (which has appeared elsewhere, as will be discussed below), Niedecker added, in line two, the words “he said,” perhaps to make clear to the intended reader (Al Millen’s daughter, after all) just who was speaking the words, whose was the gift? In this stanza, we see how the man she is considering enriches her life through sharing both knowledge and pleasure. This voice continues in the fourth stanza. We’re still talking about food, but “All things are better / flavored with bacon” is also a philosophical position, set against the school of the “thin for thought.” Pouring wine over cabbage has almost religious overtones, as a means of blessing even the humblest among us.

Finally, in the surprising fifth stanza, Niedecker shifts the focus radically. She removes from the couple, and brings in John Ruskin, a Victorian philosopher/ poet/critic she was familiar with from her wide reading. As is typical of her work, she focuses not on one of Ruskin’s public or artistic efforts, but on a more private, side note, an anecdote: a moment in his diaries when he recorded suddenly coming across wild strawberries on an expedition which had otherwise turned up little. Wild strawberries: sweet, low to the ground, an unlooked-for gift amid disappointment. It is not difficult to see a parallel to her own discovery of late life love. The poem closes with one of Niedecker’s nifty double entendres: Rose was the name of Ruskin’s beloved. In this poem, it is also simply itself, a warm, soft color which makes the grey (color of boredom, color of age) of a life easier to bear. All in all, this poem travels from the tentative start of a relationship to the full pleasure and acknowledgment of what such a late love may give to us. It is a lovely, evocative poem.

Readers of Niedecker will recognize that although “marriage” has not been published before in this form, all of these stanzas have been published in various places, including the other three handmade books of 1964. The first, third and fourth stanzas are found always together, as the first poem in each of the three other handmade books. She published these three stanzas in 1965 in Poetry magazine, in a set of five poems. It was included in her 1969 collected, T&G. The second stanza is published alone, the second poem in the other three handmade books, and then in North Central (1968) as part of the loose sequence, “Traces of Living Things.” And the Ruskin stanza is a variant on a poem, “Wild Strawberries,” which is included as the last poem in each of the other handmade books, and then printed in Origin in July 1966. “Wild Strawberries” was never collected in book form until the 2002 Collected, edited by Penberthy.

One has to be careful about making big statements on the evidence of just one poem. Certainly, in creating this new poem, Niedecker seems to be acutely sensitive to her intended audience: in this case, to the grown daughter of her (new) husband.

A second example of this sort of sensitivity to audience may surface in 1966. In Jenny Penberthy’s essay, “Writing Lake Superior” (published in Radical Vernacular: Lorine Niedecker and the Poetics of Place), writing on the generation and revision of Niedecker’s long poem, “Lake Superior,” Penberthy includes a footnote:

[Niedecker’s] 1966 Christmas card to the Neros includes an excerpt “from Circle Tour.” Strange that she should use “Circle Tour” when she had revised it in October. (78)

Why would a poet include an earlier version if there was a later revision already finished?

“Circle Tour,” an early version of what became “Lake Superior,” has been lost except for a brief excerpt. But apparently, it was written as one long, uninterrupted narrative of her trip with Al around Lake Superior. Later revisions chopped the poem into a numbered sequence and, in Penberthy’s words, “obscure[d] the contemporary travelers” (71). Penberthy notes that even the title, “Circle Tour,” “lodge[s] the poem with the human circumnavigators”(71). It is not hard to imagine that perhaps Niedecker felt for a Christmas letter, the earlier draft would stand as a sort of “what we’ve been up to this year” update. Was it more appropriate to that particular audience of one than a later, choppier and abstracted version might be? Once again, here, as with “marriage,” we find Niedecker aware of and responsive to the intimacy of a gift relationship. She intended poems she sent to friends, and these handmade books, as gifts. Perhaps she was willing to present various versions of her poems in light of their recipients, and the context in which the poem was placed?

Whatever her reason or motivation, Niedecker seems to have been willing to reimagine her poems. As Rachel Blau DuPlessis writes in her essay, “Lorine Niedecker, the Anonymous: Gender, Class, Genre, and Resistances”:

In [Niedecker’s] textual practices, she carried poems forward from volume to volume, presenting them repeatedly in different contexts, not always seeking newness, but multiple tellings…She also (though more rarely) offered different versions of some poems when she presented them in print form. These tactics are similar to multiple transmissions of an oral tradition, but play havoc with the print institution of copy text and the authorial ego-frame of “final intentions” in ways that do not (unfortunately) lead to clarity in her collected works. (Penberthy 119)

“marriage” raises questions for me, as a poet and reader. In the swamp and flood of a life, can there be, ever, one single definitive version of a poem? Should there be? Do poems write themselves linearly? What narratives do we construct as readers? And how are these questions clouded, if poet and/or reader take into account an intended audience? In a letter to Corman on May 3, 1967, Niedecker writes, “Poems are for one person to another, spoken thus, or read silently…” In the first place, “marriage” seems to have been intended for Julie, a gift. Now, as her readers, we become each that “one.” That such a characteristically brief, graceful poem may, like a pebble dropped into a pool, ripple out in many directions and for a distance, seems to me a good thing. It is a privilege to include it in the pages of Verse Wisconsin.

Works Cited

Faranda, Lisa Pater, ed.“Between Your House and Mine” The Letters of Lorine

Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960 to 1970. Durham, NC: Duke University

Press, 1986.

Penberthy, Jenny, ed. Lorine Niedecker, Woman and Poet. Orono, ME:

National Poetry Foundation, University of Maine, 1996.

Willis, Elizabeth, ed. Radical Vernacular: Lorine Niedecker and the Poetics of

Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2008.

(1903-1970) grew up on Blackhawk Island, just outside Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. Except for brief stays in New York, Madison, and Milwaukee, she lived her entire life on the banks of the Koshkonong River. Her reputation as a poet has grown steadily in the years since her death.

(1903-1970) grew up on Blackhawk Island, just outside Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. Except for brief stays in New York, Madison, and Milwaukee, she lived her entire life on the banks of the Koshkonong River. Her reputation as a poet has grown steadily in the years since her death.  Sarah Busse is a co-editor of Verse Wisconsin. Her chapbook, Given These Magics, is out from Finishing Line Press in 2010.

Sarah Busse is a co-editor of Verse Wisconsin. Her chapbook, Given These Magics, is out from Finishing Line Press in 2010.