Book Review

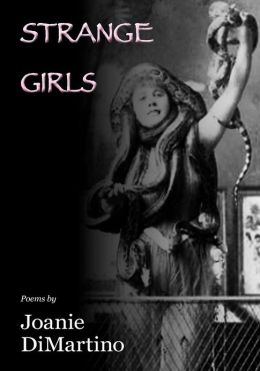

Joanie DiMartino, Strange Girls, Little Red Tree Publishing, LLC, 2010

by Marybeth Rua-Larsen

The sideshow women, or Strange Girls, as they were called, who populate Joanie DiMartino’s first full-length collection kick ass, plain and simple. From DiMartino’s own Great-Aunt Josephine, who left her husband and two children during the Depression to be a snake charmer and bareback rider with a traveling circus, to Marvelous May Wirth, Bird Millman and Lillian Leitzel, who attained the highest level of skill and precision in their respective acts and enjoyed immense popularity, these women did it their way. Their tales aren’t always happy ones, but they have a grit and determination that leaves readers in awe of their accomplishments while also understanding that sideshow artistry was a way women took control of their bodies and their lives, both economically and personally. DiMartino paints vivid portraits of these women, and while she doesn’t shy away from the seamy side of circus life for women and the challenges they faced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, she also makes them sparkle in their ambition and lust for life.

A historian by trade, DiMartino spent many years working in the history museum field, and it’s obvious that a significant amount of research went into this book. In addition to the 83 poems, there’s an introduction providing general information and a historical perspective on women in the circus, written by DiMartino herself, as well as nine pages of notes on the individual poems and a bibliography. Her extensive research is evident not just through the telling details she utilizes in the portrait poems of various performers but also through her use of circus slang and lore, and poems such as “Evetta Matthews Clowns Around,” presented in its entirety, take known facts, in this case that Mathews was the first woman clown and “shocked” 1890s audiences by wearing pink tights, and turns them into a triumph of the New Woman:

In tights that show

the curves of calves,

the sleek flesh of thigh,

dyed the same rosy hue

of her sex between,the lady jester

struts from the ring,

sits among men

on the south side

of the tent, and rejects

the ringmaster’s offer

of $5 to return.These men here offered

me $10 to remain, she

retorts, then crosses her

stockings, and lights

a cigar in the lurid

heat of spotlights.

In addition to poems about actual or imagined performers, a large number of poems focus on spiders and spider imagery and lore, so much so that it is one of the defining elements of the book and is the basis for the book’s structure and organization. Each of the book’s eight sections, called “legs,” represents one of the eight legs of a spider and explores a theme. For example, Leg 3 (such vile medicine to ingest) and Leg 5 (the gross unfortunate at dusk) focus on what women performers had to endure and the boldly wicked or heartbreaking experiences of others, respectively.

The spider imagery seems to originate from the sideshow exhibit Spidora, which was an illusion act utilizing mirrors to trick audiences into believing there was a live creature that was half woman and half spider, a woman’s head on a spider’s body. DiMartino includes an impressive array of spider natural history, mythology and lore throughout the poems to portray women sideshow performers as multifaceted creatures that are intelligent, stealthy and to be both feared and admired. In addition to 19 Spidora poems, which are told through the voice of this half woman-half spider creature, poems reference Patience Mouffet, the actual “Miss Muffet,” Arachne, of Greek mythology, the tarantella, a dance to cure venomous spider bites, and numerous others. One key poem, “Spidora Contemplates Children” presented in its entirety, encapsulates a number of these themes:

Her apartment spills over with spider

plants. She admires the long bladesthat curve over the side of terra cotta.

Each with eighty-eight legs, she muses,instead of eight. Come spring, they reproduce:

little spidery orbs, puffs of flora,on lengthy tendrils that cascade

throughout the tiny rooms, blousingback and forth in the heavy

breeze of early May afternoons:wee beasties, she whispers,

cups them in her handsand coddles the newborn sprouts

while she re-potsthem in rich soil. She longs

to swaddle her spiderlingsin silk, bind them womb-tight to her

through umbilical spinnerets,smother each one until powerless

with succulent bruises, with puncture wounds.

What starts as innocent longing turns into a love that hurts, a love that can’t help itself. Women sideshow performers lived a difficult life in many ways, though it was usually one of their own choosing and one they relished. They had more freedom than the average woman, yet they were largely shunned by respectable society and labeled promiscuous and immoral. The poem suggests that being viewed as respectable is not all it’s cracked up to be if you have to deny who you are and can’t be true to your own nature.

There are some poems, like “Carousel in Winter, ” presented in its entirety below, that focus much more on elegant and dreamy description than in making a point or providing the epiphany-moment currently in vogue:

The carved whimsy

with floating horses swift

smooth-rumped

and mottled in snow

like thinly coated powdered

sugar where leaping stallions tow

hollow sleighs

under a cold canopy

one hoof raised

teeth bared

heads in mid-toss frozen

as echoes of organ oom-pah

music swirl around each wind-

blown snowflake

the bundled girl

impatient for this chill

to end for gilded mirrors to glitter

without this wintry blizzard

for the circle

to wend

But then the circus is a place to dream, and these women were invested in making dreams come true. In a smaller, less focused collection I might wonder about the inclusion of so much lyrical dreaming, but here they are a welcome respite, a moment of reprieve from the darker side of circus life for women. It was by no means an easy life, and as DiMartino notes in her introduction, women performers, despite often being displayed in highly titillating and risqué costumes, were forced to adhere to a long list of “behavior codes,” like being signed into their rooms by 11 pm, so as not to frighten families away from performances with their “wanton” behavior and seduction of married men.

Just as many of DiMartino’s poems, though, are sharp and witty, presenting smart women who know how to take advantage of any situation or performance. In this excerpt from “An Appetite for Glass,” a glasseater likens her act to giving a blow job, noting how male audiences typically react:

Men don’t expect a geek

to know how to lick,

to take a bottle into the throat –so when my tongue begins

to slide around the neck,slip teasingly into the top,

you can see their mouths part,almost feel heartbeats

quicken, breath softened.Until I bite – crash the tip between

my teeth, while shattered dreamsengulf my mouth

and a room of desireturns to nausea:

This is a woman who enjoys shattering expectations, as many of the women in these poems do, and DiMartino does not shy away from the sexual aspects of performance and circus life. Poems such as “The Contortionist,” “Swarm” and “After Colette Performs The Flesh Outside Paris” illustrate how the illusion of nudity (or outright nudity, as in the Colette “bodice ripper” performance) was used to sell tickets. These women became masters of illusion, and it seems clear from the poems that circus women, despite the “behavior codes,” enjoyed a sexual freedom their mainstream counterparts did not, and that this kind of freedom was part of the attraction of circus life for some.

DiMartino includes just a handful of poems about her Great-Aunt Josephine, who remains a shadowy figure. Perhaps this is meant to symbolize the many women circus and sideshow artists who labored in obscurity. Still, hers is an important voice in the book and marks both the beginning and end of this journey. In “Great-Aunt Josephine: Two-Way Mirror,” DiMartino compares her aunt’s choices with her own and adds herself to this growing list of Strange Girls:

Two generations after your birth,

also divorced and shunned,I scratch my nails

down the polished metalof your circus

past, unable to dig deeperas the hot wax stings my fingers

on my own chosenBohemian path.

On both sides of this mirrorstands a Strange Girl:

According to DiMartino, “Strange Girls” was a term circus and sideshow women either self-selected or self-embraced. To be “strange” was to be your own woman, a “New Woman,” one who lived her life on her own terms, despite society’s insistence that she conform to the roles of mother and wife. It would take a Strange Girl to write this book, one that is complex and ambitious. The sheer number of women’s voices here is intoxicating. In less capable hands, it might have produced a cacophony-induced ear ache, but DiMartino is a masterful orchestrator. She allows each performer to shine, each voice to be heard, and the arrangement of poems makes the sum even greater than its parts. May we all choose this Bohemian path. May we all be Strange Girls full of ambition, devoted to artistry, and making our true natures shine.

Marybeth Rua-Larsen lives in Massachusetts and teaches part-time at Bristol Community College. Her poems, essays and reviews have been published in The Raintown Review, Crannog, and The Poetry Bus, among others. She won in the Poetry category for the 2011 Over the Edge New Writer of the Year Competition in Galway, and her chapbook Nothing In Between will be published by Barefoot Muse Press in 2014.