Book Review

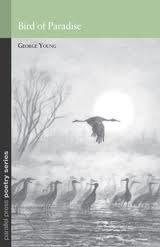

George Young, Bird of Paradise, Parallel Press, 2011

Reviewed by Richard Swanson

An on-line search with the key words Poetry Books and Birds would probably turn up a thousand hits, I’m guessing. There’s a natural symbiosis linking verse and the avian world.

The poetry books I’ve read in this category commonly describe birds as beautiful objects, awesome in color and behavior. George Young’s poems have a refreshing approach to bird-lore literature. He comes at the subject unpredictably, often with the experienced eye of a veteran birder in the field. In “To A Garter Snake” the reader only gets to the bird content in the very last of the poem. The “You,” a helpless snake, is the main character till then.

You never had a chance, on your warm rock in the late October sun.

I watch you curl around the horny talons,

watch the terrible beak bite

the back of your neck and pull your slender body straight,

watch you go, headfirst, down the throat,

watch your still wriggling tail disappear in one, two, three gulpsthen watch you fly away across a brown field,

circle

and climb to heaven—now you are a hawk.

This same sharp-edged insight appears again in a poem entitled “Audubon,” where Young describes the practical needs of the bird-painting icon, detailing John J.’s having shot a Snowy Egret so he can have it in hand to examine it better:

Later, he wires its body.

And then, as always, under the point of his brush

it becomes a languid, odd thing,

its neck stiff, a dead

thing, never the vision he held

for a moment—which wasa radiance

and which died with the bird.

These two excerpts might mislead a bird-lover into thinking Young’s vision is tainted with grimness. However, his offbeat insight can yield uplifting works. Another of his poems has him musing on finding a small, white feather on a street. What should one do with something like that? He answers: “[G]o ahead, stick/ this miracle in your hat band…for the bird, for the world, for/ yourself—saunter on, whistling.”

Similarly, he can find unusual beauty in an often-overlooked species (from “At Bosque del Apache”):

Here

on a tree stripped down to its black wires

a hundred yellow-headed blackbirdsjostle

each

spaced exactly three inches apart, each

facing the setting sun—for an instantthat tree

as full

of gold lights as Christmas…

There are lots of other species in this chapbook: birds of paradise, owls, pheasants, meadowlarks—ample fare for bird-lovers. Many of these seem to prompt a unique philosophic meditation from the author, and Young, a retired physician, has both appreciative empathy and dispassionate objectivity in viewing them.

For general readers of poetry, bird-lovers or not, Young’s poems have both vivid imagery, and well-developed themes.

Beginning poets can also find in these works outstanding models of how the arrangement of a poem can enhance a poet’s intent, tightening at times, loosening at others, floating free, isolating and then locking in certain elements, for example, in “Heart Attack,” which begins

At first a speck, high in

the sky, a speck diving on another speck.

Then through binoculars,

a peregrine,

wings folded, stooping two hundred miles

an hour

on a pigeon—

and the explosion

of feathers

as those terrible feet

reach out, grip, and stop a heart…

I suspect Young comes by this talent by instinct, he’s so good at it.

Also, beginner poets might want to jot down this quote, as a source of guidance, from Young’s “Wings”: “A poem is not a bird until it flies in the mind.” That standard certainly applies to the works in this finely wrought chapbook.

Richard Swanson is the author of two collections Men in the Nude in Socks and Not Quite Eden and a forthcoming chapbook (Paparazzi Moments), from Fireweed Press. A frequent reviewer for Verse Wisconsin, he is also the Secretary of the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets.