Book Review

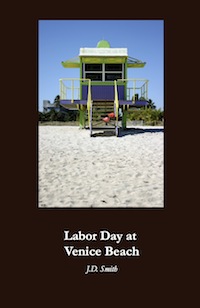

J.D. Smith, Labor Day at Venice Beach, Cherry Grove Collections, 2012

Reviewed by Carmen Germain

It’s difficult to imagine the uncluttered sandstone cliffs of the Wisconsin River before nineteenth century touts hawked rowboat trips to tourists. The ox Babe and lumberjack Paul, the shouting billboards, the crowded waterparks, and the motels with names like Curley’s Holiday Cabins have long colonized the river and forest. J. D. Smith’s third poetry collection, Labor Day at Venice Beach, begins in this setting with “First Memory,” a poem that partially redeems the Dell’s fall from grace: “Those who had brought me here / could afford this much. / They spent it, and more, / according to my need.” And the poem’s last stanza serves as guide to the rest of the poems:

In a used Oldsmobile

I fell asleep on a ride

over gravel roads

that were, if dark,

straight and real.

Divided into four sections exploring mortality, the amorality of nature, the role of citizens in country and world, and the consequences of travel in that world, the poems are “straight and real.” The pieces in the first section are moving and contain memorable images: “Here is the far country, the distant shore, / before us, the fabled, dreaded land, / the third pole left out of / navigators’ maps / and implicit in them” (“Metaphors of a Mother’s Death”).

The subsequent section argues for reconnection with the natural world, exemplified by “Elegy,” the opening lines matter-of-fact and explanatory, orienting us to time and season: “Dusk. The plangent geese migrate.” The geese “that used to bisect a continent” now settle for the night in “an office park, small oxymoron,” a landscape shaped by the language of commerce. Bulldozing for golf courses and retaining pools translates to “land development” in this tongue. The stanza closes with an image that underscores the rest of the poem: “The flocks will rest in head-tucked clusters, / low, transient monoliths, like modest gods / left by a miniature people.” With the speaker’s recognition of loss is self-consciousness and embarrassment:

Still, the land-crossing cry

persists as if to close

not a day, but a season,

and mark its loss

with a portion of the brokenness

that informs the haiku’s heart

and the weightless bone, somewhere in my heart,

that is struck and softened

by the sentimental string arrangement

that bathes the climax

of a made-for-TV film

about the latest disease

or another private distress

raised to a social issue, if not elevated:

all is forgiven, by everyone, at death’s door.

Reason and emotion are at war with each other. But then the poem jolts us: many in our culture are suspicious of deep feeling when it comes to “nature,” and the speaker internalizes this view.

Suddenly the violins cease; someone kicks over the bass drum: “¡ Pendejo que soy! Literally, in Spanish, / what a pubic hair, meaning fool, I am. / Even my confession is reduced.” The poem builds from the “pubic hair fool” to Augustine’s

“Mea saura! / Literally, what a lizard I am,

meaning the serpent’s cousin,

and hardly less intimate

with the foot-hardened ground.

Mea maxima saura!

What a great lizard I am,

shouted across the gulf

between perdition and salvation,

showing the passage that awaits

those who can summon

such heights and depths.

The speaker has another name for it, “without affecting a second language: asshole,” a name he is certain “Others might” call him as well. What a release if he could be “simple flesh” and live “untroubled,” like the woman on a radio talk show who when asked what she thought of the Iraq war, replied that she thought nothing. She had called in to give her brownie recipe on the air.

It can be alluring to live this way, to be free of news of refugee camps or despots or polar bears treading seawater, released from the obligations such news requires of us. So, too, the speaker could “look past the short flights / now joined to the landscape / like sparrows, or a soybean field.” To do so would mean depopulating this world of its “modest gods,” the beauty that moves us to pay attention, be responsible. Thus the speaker considers his voluble extremes, the shape-shifting between Hell and Heaven. How does it change anything to mourn the passage of a season, a wild way of life before the “miniature people” irrevocably descended upon the world? But it’s a devil’s bargain to be “simple flesh,” reducing the “modest gods” to “sparrows, or a soybean field.” “Elegy” is a lament for what’s gone, compromised, and lost, a poem worthy of an audience.

Other poems that stand on sturdy legs include “State of Matter” with its extended metaphor of ice, “a fifth column” working in the country of “steam and water,” and the companion poems “The Tears of Women” and “The Tears of Men.” Additional poems speak of the “fog of war” that destroys all but the generals, the battlefields and the villages that witness this blood, the vultures that are always fat.

The pieces that rely on statement to deliver messages are the less successful poems, as in “Country Data,” where the language doesn’t rise above reportage: “Imports include but are hardly limited to / manufactures and debt. / Entertainment and cash crops represent / the leading exports / in spite of thinning topsoil / and hope.” Poems should open up the world we think we know and help us experience that world differently. In his best work, Smith does this.

The title poem of the collection concludes the book with a cast of characters who might “seem interchangeable,” but are a “wheel / on untold paths of moving and being / where sand and salt water meet / in their own begetting.” Labor Day at Venice Beach thus ends in another amusement park, the poems that brought us here “straight and real.”

Carmen Germain has published in Natural Bridge, Dos Passos Review, The Madison Review, New Poets of the American West, and others, and has e-reviews in Rattle and Verse Wisconsin. Cherry Grove published These Things I Will Take with Me. She lives in the other Washington.