Book Review

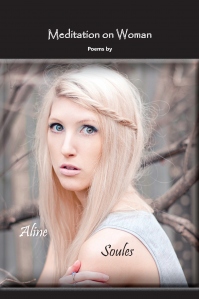

Aline Soules, Meditation on Woman, Anaphora Literary Press, 2012

by Carol Smallwood

Meditation on Woman is a collection of fifty-six prose poems to be read slowly, a few at a time, to fully appreciate their impact. Each, simply and economically written, begins with the two words, "A woman." Some of the journals that have published a version of a few of these reflective poems by this California State University, East Bay faculty member are the Kenyon Review, The Binnacle, and Poetry Midwest.

A recent Poets & Writers featured six articles in a special section in the magazine from leading writers about inspiration: the importance of slowing down, making room for contemplation, and the possibilities for discovery for the creative writer. Meditation on Woman supplies readers with examples of this in abundance as this poetry collection turns the ordinary upside down, leaving the reader, man or woman, to look at things differently.

In the opening work, "The Third Eye", woman catches the cycles of her garden:

A woman sets up her video camera, focusing it to chronicle the cycles of the garden.

A gardener turns over the winter ground. The loosened clods glisten in the sun, the damp evaporates through the day, and the earth pales to medium brown.

Green shoots push up, jagged leaves unfold, and tight buds emerge. Ants crawl over the green fists and chew their sweetness so that the peony flowers can erupt in white and pink and deeper pink, heads so heavy they drag on the ground.

“Nature” addresses the distance between pristine and artificial nature; and the suburban attitudes in “Weeds” drives a woman into the city.

"Evolution" recalls the magical-realism of Gabriel García Márquez and Isabel Allende, the blending of what is real and unreal:

A woman grows a tail. At first, it’s just a nub at the end of her spine. Doctors think it’s a bone growth, nothing to worry about. They remove it, but it grows back. The more often they remove it, the faster it returns, so she decides to live with it. When it’s a foot long, she tucks it between her legs to hide it. When it grows to four feet, she wraps it round her left leg and conceals it in wide-legged pants.

As she gets used to it, she stops hiding it. People whisper and avoid her, but eventually come to accept it. Strangers still stare or whisper, children jeer and point, but she ignores them.

A woman's connection to the world recurs in “Far and Near.” One woman “gazes out a plane window at fields quilting the landscape thirty-five thousand feet below,” while the other “hikes a woodland trail and stares into the underbrush.”

The first sees the world at a distance: "The roads make squares and rectangles around the fields. Lakes are thumbprints pressed into the land. Rivers squiggle and canals angle in thin blue lines. Tree patches are dark and fuzzy. Little towns clump together; house roofs glint in the sun."

The second sees it in close detail. "She picks a Queen Anne's lace to take home. It's umbel is so perfect, the white lace fans out in a curve that fits in her cupped hand, and the tiny black floret draws the gaze of her eye to the center of its lacy snow, like a single jet against a sky full of clouds."

Making one's own world is also reflected in "A Question of Balance" where a woman "owns the river, owns every bird that skims." In the surprising poem about a woman being roasted on a fire: "And as she turns, her eyes shimmer in tune with the heat and see in every direction. The earth, all motion, spins with her and she with it."

Readers can easily relate to: "A woman is good at guilt. Palpable and breathing, it lives in her house. It lies down and sleeps in her spare bed" and understand the mixed feelings in relationships: "The woman looks at her sister. She loves her and hates her as much as ever."

The familiar scene of waiting for an x-ray, the description of hospital gowns, the gowns spilling over in bins, the closed doors marked with signs, makes the 134 words in "Horizon" especially memorable:

A woman sits on a wooden bench, waiting to be called for an x-ray. There is no window, only walls of lockers, changing cubicles, and benches where she can wait.

She hangs her clothes in a locker and puts on a hospital gown. Sprinkled with pale blue cornflowers faded from washing, it is too short and too narrow to cover her naked body. Discarded gowns spill over the top of a bin onto the floor, waiting for someone to take them to the laundry.

The room is warm, like a sauna. Even in her naked state, she grows hotter and hotter. She leans against the wall, her skull hard against wooden slats.

She sees three closed doors, each marked by a sign:

Staff only

Wait until called

Door to the outside world

In each poem the poet is seeing herself and in the process, the universal: an activity so simple and yet complex, full of surprises and reflections of wonder. I'm looking forward to her next collection to savor, open my eyes, enjoy the company of a uniquely gifted poet. She clearly is familiar with Doris Lessing's advice: "Have you found a space, that empty space, which should surround you when you write?" Women will especially relate to this contemplative collection by Aline Soules, but they are so universal that men will appreciate them and be awed as well.

Carol Smallwood co-edited Women on Poetry: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing by Successful Women Poets (McFarland, 2012). Her poetry received a 2011 Pushcart nomination. Women Writing on Family: Tips on Writing, Teaching and Publishing, is from Key Publishing House, 2012.