Book Review

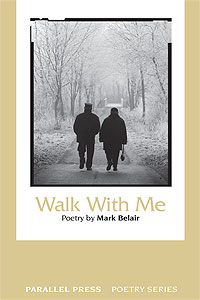

Mark Belair, Walk With Me, Parallel Press, 2012

by Timothy P. McLafferty

In his new chapbook Walk With Me, Mark Belair has crafted an offering of poems that range from his childhood in Maine, to his current life in New York City. To these poems, he brings his gathered perspectives and values, sometimes offering a powerful critique of the forces that molded him. At all times present in his poems as observer and participant, we do indeed walk with Belair, from the lost farms of Maine to the wind-swept canyons of Manhattan.

In range, Belair exhibits a freedom from group and rule: equally comfortable with tight, pared language and varied rhythm, or with prose poems, lists, and confessions, not at all afraid of adjectives, significant epiphanies, or genuine warmth. Though this freedom makes him hard to pin down and define, it also serves to open his art, refreshingly.

Events from his childhood are more than reverie—“The Word” describes the adrenaline rush of riding a Ferris wheel: the height and vista, the possible danger, and the slow, jaunty ride back down to earth, where a seven-year-old Belair experiences the frisson of premonition—a window into the circular nature of life’s exhilarating highs and lows and the welcomed feel of a return to earth:

the whole circular event feels like

some weird premonition

except you don’t know that word

yet so don’t know what it was you

just felt; what it was just happened.

“The Lemon Square” takes a wry look at snobbery in his hometown, clearly unknown, at least, to some of its practitioners. In it, we see the inhibitions applied to a four year old, who, though he delights in his lemon square, has learned that maintaining a veneer of restraint has its rewards:

then we went to Legere’s where my parents

would chatter in a French older than what they speak in Paris,

discussing matters of health, news of Quebec, the sins of ungrateful children—

but never the mill or its Protestant owners

who, in fact, ran our lives.We wouldn’t stoop to complain.

Wouldn’t give them the satisfaction.

Gave an honest day’s work

for an honest day’s pay,

asked from them nothing more

and gave to them nothing else,

an arrangement that mutually worked out:

they got skilled, reliable workers

and we, left otherwise alone,

were free to keep up

our language, our culture, our religion

despite our financial duress,

which we refused to show:

Sunday mornings, properly dressed,

we displayed to each other

(and to the Protestant snobs)

our pride in being French-Canadian Catholics.So I, a grateful child, carried

my lemon square home

like a little gentleman, politely

nodding to passersby, never

cracking an anticipatory smile, never

letting on to the slightest desire.And even later, at home, when I finally

took my lemon square out and ate it,

I knew what was proper

to keep in the bag:

my joy.

A brilliant example of Dichten = condensare, “The Underside” takes off with brisk rhythm, as a young Belair chases his football into the crawlspace beneath the family cottage. We move with him, fast and sure into darkness, where, taking stock of his environment, the beat slows and our eyes adjust, offering us a detailed look at the structure’s underside and the detritus found there. There, in the dark, it becomes clear that things have an organic and natural duality:

Limp leaves on damp dirt

hard-packed beneath our cottage porch

reeked of fall’s underside

as I crawled under there

for a football I’d booted to no one,my parents talking up above,

inside, their voices so muffled,

they seem not quite real or,

at least, not nearly as real as this

Belair shines brightest in two of his most intimate poems: “The Hermit” and “Nearness.” These spare and elegant poems reveal inner details, partial smokescreens, and wisps of experience. Dark and poignant in the telling, compelling in what’s left unsaid, in these poems, as readers, we experience the very essence of what William Carlos Williams meant, when in “To Daphne and Virginia,” he wrote, “Be patient that I address you in a poem, there is no other fit medium.”

Belair is destined to chart his life’s journey in his poetry—observing and experiencing: one part cautious and restrained French-Canadian, and the other, loose and flowing with New York City hip. Accepting and anticipating unforeseen convergences, optimistic, allegiant to no muse but his own, and most content with the ride; a ride best summed up by Belair himself in “the day trip”:

safety seats / juice packs / buckets and shovels / picture books / sunglasses / gasoline / crackers / string cheese / wet ones / cooler / pillows / flashlight / whatever cash we can muster / a bag for garbage / bags to throw up in / an empty peanut butter jar for pee / wiffle ball / frisbee / beach umbrella / swimmies / sun block / boogie boards stretched across the rear windshield / flip-flops / beach ball / beach chairs / beach blanket / towels / newspapers we’ll never get to read

how long till we get there / will the water be cold / is god real or just a name for stuff we don’t know / i think my leg died / i want a pet ferret / mom / dad / what’s a quick blow job

then we park / arduously unload and / carrying everything at once / advance like an ambulatory pop sculpture to a clear beach spot and / exhausted / drop it all

stressed / exasperated / patience worn thin / we look up as the boys / darting quick-footed in the hot sand / rush toward the cold waves / rolling to meet their clean little bodies / gleaming in the sun / and we know / just before running to save them from drowning / know in a moment that / like a sea breeze / cleanses us

this is bliss

Tim McLafferty lives in NYC and is a professional drummer. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Forge, The Portland Review, Talking River, Soundings East, and RiverSedge. Ongoing from July, he will be the cover artist for Forge.