Book Review

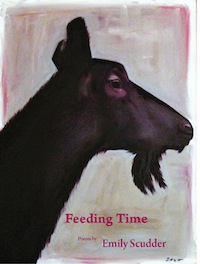

Feeding Time by Emily Scudder. Pecan Grove Press, 2011. $15

Reviewed by Moira Richards

The cover and title of this collection grab me right off. Then, in the acknowledgements listings, I see the poet’s thanks to her husband—for being her goat. A quick scan of the contents yields no poem with a goat in the title, but I do find Feeding Time. No clue here though; it’s a poem about stingrays feeding—a lovely slurpy, sensory piece of concrete poetry in the shape of a ray—but it’s not about goats. And not, I think, clue to the title.

Next I read up on goats at Google and discover them to be epicurean nibblers that thrive on variety and choose, carefully, just the tastiest, most tender bits of whatever is on offer. And this poet shares with us—connoisseur goats—a gourmet selection of observations in the first part of her book, and of more reflective musings in the second part.

In an interesting approach, Emily Scudder explores a variety of subjects in the first section of this eclectic collection and then revisits many of them in the second—a device that had me flipping back and forth, eager to trace the subtleties in the flow of undercurrents.

The opening poem reverberates with another piece near the end of the book. The first begins conversationally and sets a desultory mood with its stream-of-conscious wanderings of thoughts:

Seagulls bore me. I like this boredom.

The mind can wander, like this.Snails latch onto other snails. Or a rock.

Clump.With drop lines, kids fish.

Pull them up. Throw them back."Transitory Adhesion"

Much later, Scudder returns to seagulls, returns perhaps to the same beach as in the first poem. But now the narrator seems more in tune with the surroundings, more at one with the birds

Low tide has become a resting place, a harbor for things I love—

dead fish, clumps of empty shells, a beached orange catamaran,and always, the gulls are here.

There is salt in their song – I hear it on the inhale

…and someday, too, I might gulp the harbour air

—and simplify everything"What the Gulls Know"

Sometimes the link between poems about a particular topic works as an expanding of the narrator’s initial observation, into a disclosing of her underlying feelings. In part I you’ll find the narrator looking at, describing, a man, J:

When he sleeps I like to look at him, his long legs

like the ocean, blue jeaned, flat out.J. sleeps best in the afternoon sun.

He looks like summer waves, if a person can."In His Sleep"

then later, Part II revisits J. with images of him awake and about his daily life…

J. has wings.

Others see them too

(you can’t hide for long what makes

you different).J. is a tall man. And he kisses me.

"Valentine"

Explorations of these pairings tease out some subtext behind the poems’ words. Many of the pieces in the collection revolve around parenting and children and here, some ill-behaved pet frogs ‘doing the nasty’ in the magnified viewing area of an indoor aquarium get short shrift:

The fire-bellied frogs are croaking

wild-like in my daughter’s room.

I thought it was the radiator. I can’t take it.

I tell her they are dying and dump themin the garden, but spot them sexing-it-up,

bellies aflame, igniting the rhododendrons."The Fire-Bellied Frogs"

And in the second section, children’s pets again and the narrator fantasises (just for a while) about ways to kill off the hamsters in a way that illuminates the pent-up unsaid frustrations of the earlier poem:

Each night I kill the hamsters.

Drop them out the window.

Feed them to a snake.

Dehydrate them.

Hammer their heads dead

In a brown paper bag.

The thought passes.

"Too Many"

In some pairings the later piece adds a depth, an extra facet not quite explanation, to an earlier, already very moving, poem.

He carried his sister in a bag

to the cemetery, sprinkled her

into a pond where the ducks

flew down and ate her up.

“She always liked duck” he said.

It was the right thing to do."Cremations"

In the second part of the collection:

some think

we all have another

who shares our deepest secret

who tunnels miles to deliver the message

written in invisible ink"Belief"

This may not be how the poet intended her collection to be appreciated, but it gave me great pleasure to read it, to nibble at it in this way.

Moira Richards lives in South Africa and hangs out here: http://www.darlingtonrichards.com and here: http://www.redroom.com/author/moira-richards. She, with Norman Darlington of Ireland, edits and publishes the annual Journal of Renga & Renku.