Book Review

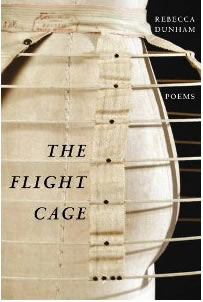

The Flight Cage by Rebecca Dunham. Tupelo Press, 2010. $16.95

Reviewed by Linda Aschbrenner

Feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 - 1797) speaks to us through Rebecca Dunham’s persona poems in her book, The Flight Cage. Dunham, who teaches in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, won the T.S. Eliot Prize from Truman State University Press in 2006 for her first book, The Miniature Room.

The Flight Cage haunts, written in voices of long-departed women who dared to question the status quo or who survived it. Dunham’s writing is fluid, lilting, image rich while she frequently selects words, phrases, and sentence structure to coincide with the speaker’s era.

In the book’s front matter, Dunham includes a quote from Mary Wollstonecraft’s groundbreaking 1792 treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Women: “Confined, then, in cages like the feathered race, they have nothing to do but plume themselves and stalk with mock majesty from perch to perch.” Wollstonecraft had reason to promote educational and social equality for women based on her own life—her brothers learned literature, classical languages, and mathematics at school while she, a female, was restricted to basic reading and mathematics and had instruction in sewing. From the first poem, also in the front matter, “Mary Wollstonecraft in Flight”: “I will not be confined, / content to peacock and preen // my manifold eyes.” Indeed, both Wollstonecraft and Dunham see with comprehending eyes, seeing a myriad of directions, multifaceted, multitudinous possibilities.

Wollstonecraft became a writer with the support and encouragement of her London publisher, Joseph Johnson, who also published the works of Thomas Paine, William Blake, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Two poems about Wollstonecraft appear in the first section, “Terra Incognita,” and three in the third section, “Séance.” However, it is the middle section, “A Short Residence,” that Dunham devotes exclusively to Wollstonecraft inspiration. “A Short Residence” is comprised of 25 crown persona poems based on Wollstonecraft’s travel book, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, itself 25 letters from her three months of travel in 1795. Wollstonecraft’s travel book was popular upon publication as it combined travel writing with philosophy and memoir. In these letters, Wollstonecraft also examined the role of women and responded to the disintegration of her relationship with her lover, Gilbert Imlay, the father of her child, Fanny. Dunham's poems invoke life as a short residence—fleeting, fleeting, like all trips and journeys.

Dunham uses phrases and sentences from Wollstonecraft’s book, placing them in italics. The 25 poems in “A Short Residence” are all written in three stanzas of quintains. In “Letter 6,” Wollstonecraft contemplates the future of her daughter Fanny (who made the journey from England with her along with her maid). This poem begins:

My child watches the salt pork sizzle.

A dozen potatoes fill the sink and I give

each its careful attention, feeding dirt

to the drain. Hapless woman! what a fate is thine!

Years of scrubbing. Clay pots crowd

my kitchen shelves, unglazed and pink

as my daughter’s skin, fresh from the tub.

Their contorted mouths beg to be

filled. I dread to unfold her mind, lest

it should render her unfit for the world she is

to inhabit. (24)

Daughter Fanny committed suicide at age 22. Mary Wollstonecraft had two suicide attempts before she died at age 38, eleven days after giving birth to her second child, daughter Mary Godwin, who grew up to write Frankenstein and marry Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The grand opportunity with persona poems: to mix biography with one’s own life and thoughts—it’s poetry as interpretation, fiction, biography, and autobiography all combined in various hues and measures. “Letter 24” from “A Short Residence”:

They fill the sky, fireflies netting

the house and us inside it. All

the necessities of life are here extravagantly

dear. My son sleeps in his crib,

breathing. All day I teach him rules,

permanence. A spoon still exists

when it drops and people don’t vanish

if they fall out of sight. But it feels

like a lie, dishonorable as gambling,

to promise him people return. It is

my own fear that makes his quiet form

a relief, right there where I left him.

It is magic. Lift the blanket

and he reappears: bottom up, legs

tucked beneath, genuflecting in sleep. (42)

And from the poem, “Alfoxden,” section one, based on Dorothy Wordsworth:

My journal pleases Wm., each day’s entry

a small bud and I am glad. Its deckle-

edged leaves seem to me, at times, almost

to rattle between my pinched fingers like

the packets I empty over earth’s harrowed

mound. My seed-black script smatters

the page. Leech-gatherer and night-piece

alike fly loose, words lifted and blown

by a wind, to fertilize some other’s ground. (15)

How much did William Wordsworth borrow from his sister’s journals? So many questions these poems elicit. How difficult was it to be a pioneer for women’s rights in 1792?

Dunham also writes poems inspired by Bess Wollstonecraft (Mary’s sister), Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860 –1935, American feminist writer and lecturer), Elsie Viola Kachel (1886–1963, model for 1916 “Mercury” dime, wife of poet Wallace Stevens), Dorothy Wordsworth (1771 - 1855, English writer), Daphne du Maurier (1907 - 1989, British novelist and playwright), Anna Akhmatova (1889 - 1996, Russian poet, memorist), Sarah Good (1653 - 1692, American, accused of witchcraft), Ann Putnam (1679 - 1716, American, accuser at Salem Witch Trials).

This poetry is not a dry accounting of lives; I have included dry facts here not found in Dunham’s book. Such an art to mix biography, autobiography, fiction, and poetry and realize music as the end result. As Sherod Santos stated in an interview about writing (in Valparaiso Poetry Review): “After all, one of poetry’s greatest charms resides in the mystery of what, without saying it, it somehow manages to say. And this occurs precisely because a poem’s meanings are transmitted not through its literal sense, but through its meta-linguistic effects—the associative pattern of its images, the phonic spell and resonance of its lines, the suggestive gulf that arises out of its resistance to interpretation. Which is another way of saying that, when it comes to the facts of a poet’s life, ‘reticence’ in a poem is often far more communicative than ‘explicitness’” (“An Interview of Sherod Santos” by Andrew Mulvania, conducted by e-mail in October and November 2002).

Readers will appreciate Dunham’s four pages of “Notes” with this history, literature imbued poetry. The immediate impulse upon finishing The Flight Cage is not to reread it, but to find three additional books: Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women and Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, along with any biography of Wollstonecraft—then, to become reacquainted with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poetry (not read for decades). From there, to seek information about Wollstonecraft’s publisher, Joseph Johnson, and on and on and on. Dunham’s poetry provides inspiration to explore obstacles and achievements in past centuries and to search for other poets currently writing in this genre of extended biographical / historical persona poems.

Linda Aschbrenner is the editor/publisher of Marsh River Editions. She edited and published the poetry journal Free Verse from 1998 to 2009 which now continues as Verse Wisconsin.