Six Poems

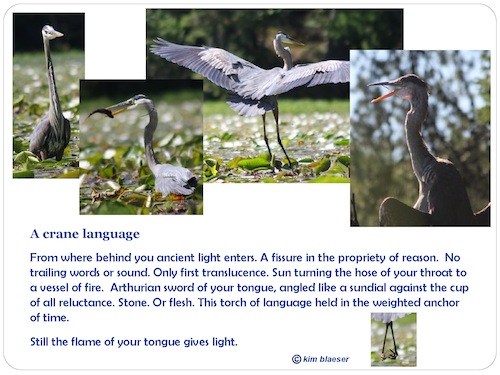

A crane language

After Words

i.

Somewhere the talk of death

is exact,

a simple exchange:

Bullet for body.

Disease = death.

Sometimes the options

multiply

in rock-paper-scissors contests:

Early detection covers cancer.

Or in quid pro quo logic:

Take one breast for promise

to attend son’s wedding.

The math of afterlife

similarly has many formulas.

Dead = Dead.

Body gone, soul survives.

Heaven or hell.

Haunting.

Reincarnation.

Ceremonial after words—

Eternal rest grant unto them.

Meet the cacophony of ritual:

funerary, pallbearer, shroud.

And absence is given new form:

Urns. Mausoleums. Sky Burials.

May the road rise up to meet you.

Incense. Mourner’s Kaddish. Columbaria.

Dust to dust.

ii.

Where Sufi whirling

spins into Irish bagpipes

into the organ’s Old Rugged Cross

into the grey fog of human longing:

The after and before.

Now and nothingness.

This world, the next.

A father’s wrinkled hand turning cold.

The moment she turns the key to a quiet house.

A room made only of food and flowers.

A dog pacing at the window.

No keening or solemn song

lifts the steering column from a chest

keeps age at endless afternoon tea.

But it is a language of afterwards

a slow walk to a fresh swell of dark soil.

Because one year I was a mother

of toddlers, we talked of dog heaven

on the cabin bed while we searched

the wood-planked ceiling for pictures

in knots and lines. No less real

were the balloons and fishing poles

we found, no less real than the frog graves

and hamster graves and sweet sad

puppy dog graves we dug.

What I mean is hold on.

Flood the cracked walkway

of the drive-by shooting victim

with flowers of every denomination.

This year stop your fuel efficient car

at the Wisconsin’s earthen effigy mounds.

What I mean is spend wisely.

Ink your unique fingerprint;

then touch that known flesh

to anonymous marble names

on the Vietnam War memorial.

What I mean is another verse

of that song you hum while driving.

What I mean is less than this paper,

less than these words that I write.

iii.

Because the smallness of our being

is our only greatness.

Because one night I was in a room

listening until only one heart beat.

Because in these last years I’ve

worn and worn and nearly worn out

my black funeral shoes.

Because the gesture of after words

means the same thing no matter

who speaks them.

Because faith belief forever

are only words, no matter.

Because matter disappears

always and eventually.

Because action is not matter

but energy

that spent, changes being.

And if death, too, is a change of being

perhaps action counts.

And if death is a land of unknowing,

perhaps we do well to live with uncertainty.

And if death is a forested land,

it would be good to learn trees.

And if death is a kingdom,

it would be good to practice service.

And if death is a foreign state

we should loosen allegiance to this one.

And if the soul leaves our body

then we must rehearse goodbye.

On Climbing PetroglyphsI.

Newly twelve with size seven feet

dangling beside mine off the rock

ledge, legerdemain of self knowledge.

How do I say anything—magic

words you might need to hear?

With flute-playing, green-painted nails

your child’s fingers reach to span the range

of carmel-colored women in our past.

Innocently you hold those ghost hands:

each story a truce we’ve made with loss.

How can I tell you there were others?Big-boned women who might try

to push out hips in your runner’s body.

Women who will betray you for men,

a bottle, or because they love you

love you, don’t want to see you disappointed

in life, so will hold you, hold you hostage

with words, words tangled around courage

duty or money. When should I show you

my own flesh cut and scarred on the barbs

of belonging and love’s oldest language?II.

No, let us dangle here yet, dawdle

for an amber moment while notes shimmer

sweetly captured in turquoise flute songs—

the score of a past we mark together.

No words whispered yet beyond these painted

untainted rock images of ancients: sun, bird, hunter.

Spirit lines that copper us to an infinity.

Endurance. Your dangling. Mine.

Before the floor of our becoming.

Perhaps even poets must learn silence,

that innocence, that space before speaking.

Dreams of Water Bodies

Muskrat—Wazhashk,

small whiskered swimmer,

you, a fluid arrow crossing waterways

with the simple determination

of one who has dived

purple deep into mythic quest.

Belittled or despised

as water rat on land;

hero of our Anishinaabeg people

in animal tales, creation stories

whose tellers open slowly,

magically like within a dream,

your tiny clenched fist

so all water tribes might believe.

See the small grains of sand—

Ah, only those poor few—

but they become our turtle island

this good and well-dreamed land

where we stand in this moment

on the edge of so many bodies of water

and watch Wazhashk, our brother,

slip through pools and streams and lakes

this marshland earth hallowed by

the memory

the telling

the hope

the dive

of sleek-whiskered-swimmers

who mark a dark path.

And sometimes in our water dreams

we pitiful land-dwellers

in longing

recall, and singing

make spirits ready

to follow:

bakobii.*

*Go down into the water.

Copper crane bodies

Copper crane bodies

ride impossible stilt legs

through fields of June.

Angles of Being

It’s all angle after all.

What we see

and miss.

The leaf bird

limed and shadowed

to match

every other

green upturned hand

blooming on the August tree

Indecipherable

even when wings flutter

like leaves in breeze.

Or the silhouette

dark and curved

on the bare oak.

Beak,

parted tail,

each mistakable

for knot

branch

or twig.

Only if they exit the scene

unblend

isolate themselves

against too blue sky

does the game

of hidden pictures

end.

Ah, angles.

Tell all

or tell it slant.

What we

dream

appear

or inverted

seem to be.

—Kimberly Blaeser