Book Review

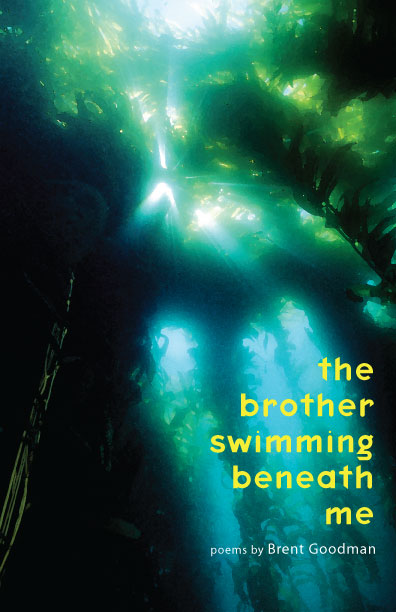

The Brother Swimming Beneath Me by Brent Goodman, Black Lawrence Press, 2009. $14

Reviewed by Noel Sloboda

In The Brother Swimming Beneath Me, Brent Goodman’s first and last poems caution readers against looking for meaning beyond this life. The speaker of the opening work, “Another Prayer,” declares, “there is no afterlife,” before concluding that “When we die we turn inside out and call / this turning a tunnel made of light.” In “[past lives]”—the last of a series of prose poems in the third (and final) section of the book—the speaker warns: “Best not to blame past lives for migraines, luck, regret, or déjà vu.” Between the frame of these two poems, Goodman repeatedly struggles against the human impulse toward transcendence, while embracing the moment and reveling in the mysteries of physical sensation.

The title suggests a focus on Goodman’s deceased brother, Mark, who frequently appears in The Brother Swimming Beneath Me. In “Maier” (Mark’s Hebrew name), Goodman describes a young man donating marrow for his sick sibling: “They drew the seeds of your new blood / by hammering hollow nails through skin / to reach the dark marrow inside my bones.” The speaker of “Evaporation” recalls how his “dropout brother” once impulsively swallowed “a mouthful of freon [sic]”— something that makes no more sense (“What were you thinking?”) than a teenaged boy dying of leukemia. Yet several of Goodman’s poems, from “First Queer Poem” to “’Armless Iraqi Boy Bears No Grudges for U.S. Bombing,’” widen the scope, making this collection more than a series of domestic elegies. And no matter what his ostensible subject, Goodman is drawn not to the ghosts of the past but to the living. He keeps readers always tethered to the “now” by dramatizing strong impressions that remind us we are both alive and mortal.

In “Oysters,” for example, the speaker sits at a hotel bar and finds his mind first drifting in “memory,” then clamoring for new experiences: “how I long after dark to roam this distant city / searching for another skin to press into my own.” However, he quickly recognizes that he will never be fully satisfied, since “what we want / will always share the moon with the sea, each small desire / emptying into something curved and waiting to fill again.” It is not longing for what has been or what could be that should be embraced, but the vividness of the “plump briny flesh glistening in blue-white / iridescent light.” Even though the oyster inspires feelings of nostalgia and yearning, its power is physical, dependent upon the senses. The play of sound in the alliterated “l’s” and in the rhyme of “white” and “light” imbues the lines with their own sensuous power.

Again and again, the workings of the body fascinate Goodman—to the point where little else seems to matter. Of particular interest is blood, the ultimate source of vitality. In “Robin Egg Blue,” the speaker simultaneously recounts cracking open bird eggs and a messy, adolescent sexual encounter: “I see your skin has broken—a crescent impression / welling the blood-purple half circle of some poor / embryo.” Similarly, “Blood Poisoning” portrays a near-fatal dog bite (“my small death”), an encounter that makes the speaker mindful of his impermanence: “One incisor sank into my palm and punctured / my lifeline. The gray death traced my veins up / my left arm to my shoulder, inches from my / heart.” Here, the break between “punctured” and “my lifeline” registers the speaker’s newfound sense of transience; and the enjambment of “heart” suggests a newfound appreciation for the engine that pumps the fluid of life.

Geography also plays an important role in Goodman’s work. In “Maps,” the speaker repeatedly visits an intersection where he nearly lost his life after running a stop sign, a place where he feels animated, in touch with the world: “Now every night / I approach that frightened intersection / with full attention.” A comparable sense of place anchors pieces like “Why I Can’t Write a Paris Poem,” which celebrates the ineffable quality of the city. Or, take “Wisconsin Triptych,” an ekphrastic poem inspired by the painting of David Lenz. It orients readers to the state using figures that link people and objects, employing both a “barbed wire fence and…gently crossed arms” as topographical reference points. In the prose poem “[in Europe everything’s different],” the speaker insists: “Sell me postcards and collectable brass landmark miniatures. Show me on this map where it says You Are Here.”

Goodman shifts adroitly from works of less than 10 lines (“Mayfly,” “Cicada”) to sprawling compositions that span several pages (“Maier”). And his voice is engaging throughout the 42 poems in this collection, energized but controlled, as he grapples with how to capture sensations tied to food, love, and travel. The prose poems of the “spiral course” feel slightly less animated than the richly varied ones of the first two sections, “Narrowly Missing the Moon” and “Evaporation.” However, they embrace life with the same fervor, cautioning us against becoming “robots” with “fleshmatic skin,” helping us to appreciate language as a means of capturing and invigorating experience. Again in the final section, Goodman acknowledges the natural inclination to seek something beyond this life (see “[famous last words]”), even as he foregrounds what we will miss if we spend too much time on yesterday and tomorrow. That said, Goodman’s poems do have memory. But it’s living memory, found in blood and in fluids shared with lovers, friends, and family—and this living memory is presented by a voice that will continue to ring out and to compel interest, long after readers have finished The Brother Swimming Beneath Me.

Noel Sloboda lives in Pennsylvania, where he teaches at Penn State York and serves as dramaturg for the Harrisburg Shakespeare Company. He is the author of the poetry collection Shell Games (sunnyoutside, 2008) and the chapbooks Stages (sunnyoutside, 2010) and Of Things Passed (Finishing Line Press, 2010).